John Cotton Dana was not pleased. By his lights, the American art museum had fallen woefully short of its potential. Too gloomy by half, it was far too remote and “dogmatic” an institution to affect the lives of most modern-day Americans. Housed in a building that “oppresses us,” the museum had become little more than a “mausoleum of curios.” It could do better, insisted the founder and director of the Newark Museum in 1917. Much better. “Surely the function of a public art museum is the making of life more interesting, joyful and wholesome.”

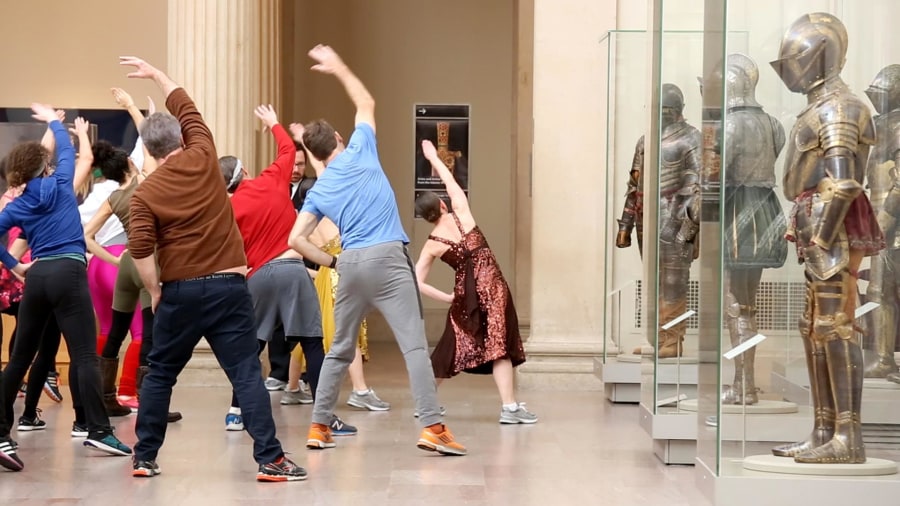

An art tour, a performance piece and a full-fledged, 45 minute exercise session bundled into one, the “museum workout” takes place in the early morning hours, when the Met has not yet opened to the public. To the sound of the Bee Gees and other pop groups with an equally strong beat, a small band of participants, led by Monica Bill Barnes and Ann Bass, two glorious professional dancers, canters through the museum’s extensive first floor galleries, engaging nearly every one of the senses.

I had the good fortune to participate in a “museum workout” this past Sunday morning (tickets are hard to come by) and can’t stop smiling. I attribute some of my good spirits to the release of endorphins -- the workout was no ‘walk in the park’ -- and some of it to having the mighty Met to myself. (Well, almost. A clutch of Met employees wearing “yield to the dance” t-shirts was positioned along the two-mile route to make sure that none of us “yielded” to the demanding, nonstop pace and fell too far behind.)

Power-walking at the Met rather than at the mall or in the nearby park felt heady, perhaps a tad transgressive. And when we assembled in front of a painting or an object to indulge in the gymnastic equivalent of an homage, stretching this way and that, or standing on one leg and then the other, I even felt a wee bit silly.

And yet, the experience worked. Powerfully. We moved, the art stood still, and then, before you could spell “M-e- t-r- o-p- o-l- i-t- a-n,” there we were, lying prone on the marble floor of the light-filled American Wing, taking it all in, one exhalation at a time.

John Cotton Dana would have been thrilled.