I’ve been to a fair number of academic gatherings in my day: conferences and “un-conferences,” workshops, symposia and seminars. By now, I know pretty much what to expect. Sometimes, the proceedings take the form of panel discussions; at other times, frontal lectures are de rigueur and, of course, there’s the inevitable keynote presentation. Sure, you’re bound to pick up a new idea along the way or come face to face with a colleague whose work you know only via the printed page or online discussion groups. But that’s about as exciting as it gets. For the most part, academic gatherings tend to be more dutiful than fun.

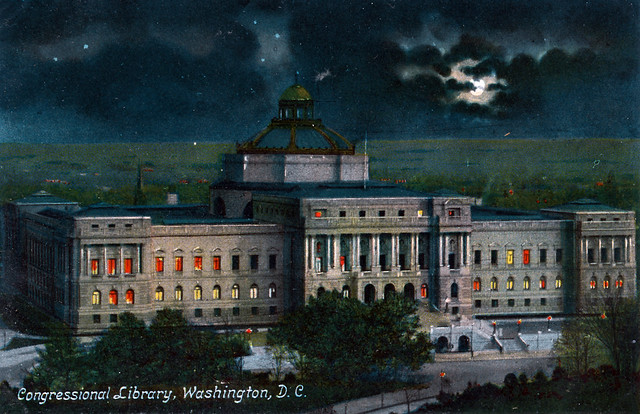

Last week’s 15th anniversary celebration of the Library of Congress’s John W. Kluge Center -- ScholarFest LOC, it was called -- was entirely different. It offered its participants, of which I was one, an entirely new form of scholarly exchange: lightning conversation. Much like speed-dating, this entailed a swift-paced give-n-take, a search for common ground, between two people who were not only unacquainted but on markedly different levels of the academic hierarchy.

As you can well imagine, the prospect of being up on a stage chatting away without the benefit (read: safety net) of a lectern, a set of well-prepared remarks and the gift of time had most of us -- both senior and junior colleagues alike -- in a tizzy. An exercise in spontaneity -- and in concision -- it called on skills we hadn’t honed in quite some time. No wonder the room was abuzz in anticipation. Much as we reassured ourselves and one another that we were not being graded on how well we performed, we knew deep down that these lightning conversations tested our mettle.

Most of us, I’m happy to say, passed with flying colors. Once we relaxed our shoulders and our perspective, we might even have enjoyed ourselves. Academics, after all, are not only good talkers. As ScholarFest made clear, we’re fast talkers, too.