Many moons ago, while a graduate student, I first came across references to the alleged cultural impoverishment of the Jews whose languages, it was said, lacked a vocabulary of botanical terms.

That notion has stayed with me ever since. Most recently, it piqued my interest in attending “Songs of Sacred Time,” a concert of Jewish music at Manhattan’s JCC to mark Tu B’Shevat, “Jewish Arbor Day,” the “New Year of the Trees.” I didn’t expect much.

Boy, was I proven wrong. Wide-ranging in subject and in musicality, the songs presented at this concert were drawn from Yiddish and Ladino, Hebrew and Arabic and spanned the centuries as well as the globe. Some took the form of lively, upbeat folk songs, others were far more rueful, contemplative, even yearning.

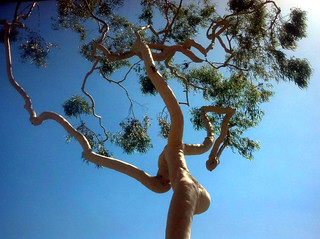

Every one was performed with exquisite skill and sensitivity by the singers -- Hazzan Ayelet Porzecanski, Rabbi Jessica Kate Meyer and Rabbi J. Rolando Matalon -- and the musicians -- Daniel Ori on bass, Uri Sharlin on accordion, Shane Shanahan on percussion. Under the skillful music direction of guitarist Dan Nadel, chestnuts such as Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “It Might As Well Be Spring,” and Naomi Shemer’s “Horshat HaEkaliptus,” came vividly to life, while little-known treasures from Afghanistan and Libya, among them “Shochanet BaSadeh,” held us rapt.

Mesmerizing and heartening in equal measure, “Songs of Sacred Time” highlighted the richness and variety of Jewish musical expression. What’s more, the sight of a young generation of artists in thrall to its textures and rhythms was marvelous to behold. To all those doomsayers out there, to all those who insist that contemporary Jewish life is on the decline, look again. And listen.

Jewish culture is in full flower.