Stories about Jewish books don’t often appear in the news, but within the past few days there have been not one, but two, feature articles about them.

Exulting in the 52 treasures on view, many of them illuminated Hebrew manuscripts and some that date as far back as the 11th century, the Times’ chief culture critic -- who will soon be visiting GW for a series of workshops and talks -- found much that pleased the eye, engaged the intellect, and buoyed the spirit.

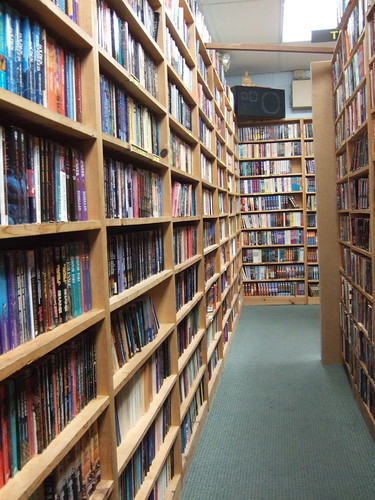

The second piece is a study in contrast. Written by Paul Berger, it appeared on the front page of The Forward and took as its subject the recent decision by the American Jewish Committee to deaccession its once storied research library.

Its shelves filled with mimeographed reports, cassette tapes, and other items whose preciousness stemmed from their contemporaneity rather than their historicity or aesthetic appeal, the AJC’s Library was meant to be used rather than contemplated. Little wonder, then, that sadness suffuses Berger’s account, along with the merest whiff -- a frisson -- of something potentially scandalous.

But that’s not how I choose to read it. Instead, I prefer to juxtapose these two stories of two different collections with two entirely different outcomes and to read them as two halves of a cautionary tale: the fate of the Jewish book, whether grand or quotidian, resides with us.