It so happened this year that Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, coincided with New York’s Fashion Week, prompting some eagle-eyed observers to trumpet the possibility of a showdown between the “shofar and the shows,” a clash between the “Goddess of Fashion” and the God of the patriarchs and matriarchs.

That didn’t happen, of course. For the most part, those participants who were directly affected by the calendrical conflict made their peace with it. Some stayed away from the runway, others adjusted their schedules and still others clucked their tongues in dismay.

What no one did, near as I can tell, was launch a public protest. What a missed opportunity! Way back in May, when Fashion Week’s schedule was first announced, its sponsors issued the following, rather tepid, statement:

The CFDA greatly respects and understands the importance of this holiday but, given the international calendar of European shows directly after New York, we do not have the option to shift the dates later. We realize that the observance of the holiday will impact some in their ability to attend or present shows -- but we are asking that everyone please work with us to make this situation work as best as possible.

Here’s a situation in which globalization trumps both localism and history -- and no one says ‘boo.’ Once upon a time, the garment industry and with it, the triumph of American ready-to-wear was not only vital to the economic well-being of the Empire City, it was also an industry peopled by Jewish manufacturers, factors, cutters, button-hole makers and union leaders, an industry as sensitive to the rhythms of the Jewish calendar as it was to the vagaries of fashion.

Revolutionizing the way the nation dressed, the garment industry proudly boasted of having transformed the American woman into the “best-dressed average woman in the world,” and her menfolk into men about town. Immigrants were particularly attentive to the magic of ready-to-wear: “Cinderella clothes,” one Jewish immigrant writer called them.

Consigned to the dustbin of history, along with the corsets, stockings, feathers and furbelows of yesteryear, these kinds of sentiments seem to have no place in a world where globalization now rules the roost and age-old religious traditions can be dismissed out of hand as if they were merely an inconvenience or, worse still, just one more commodity.

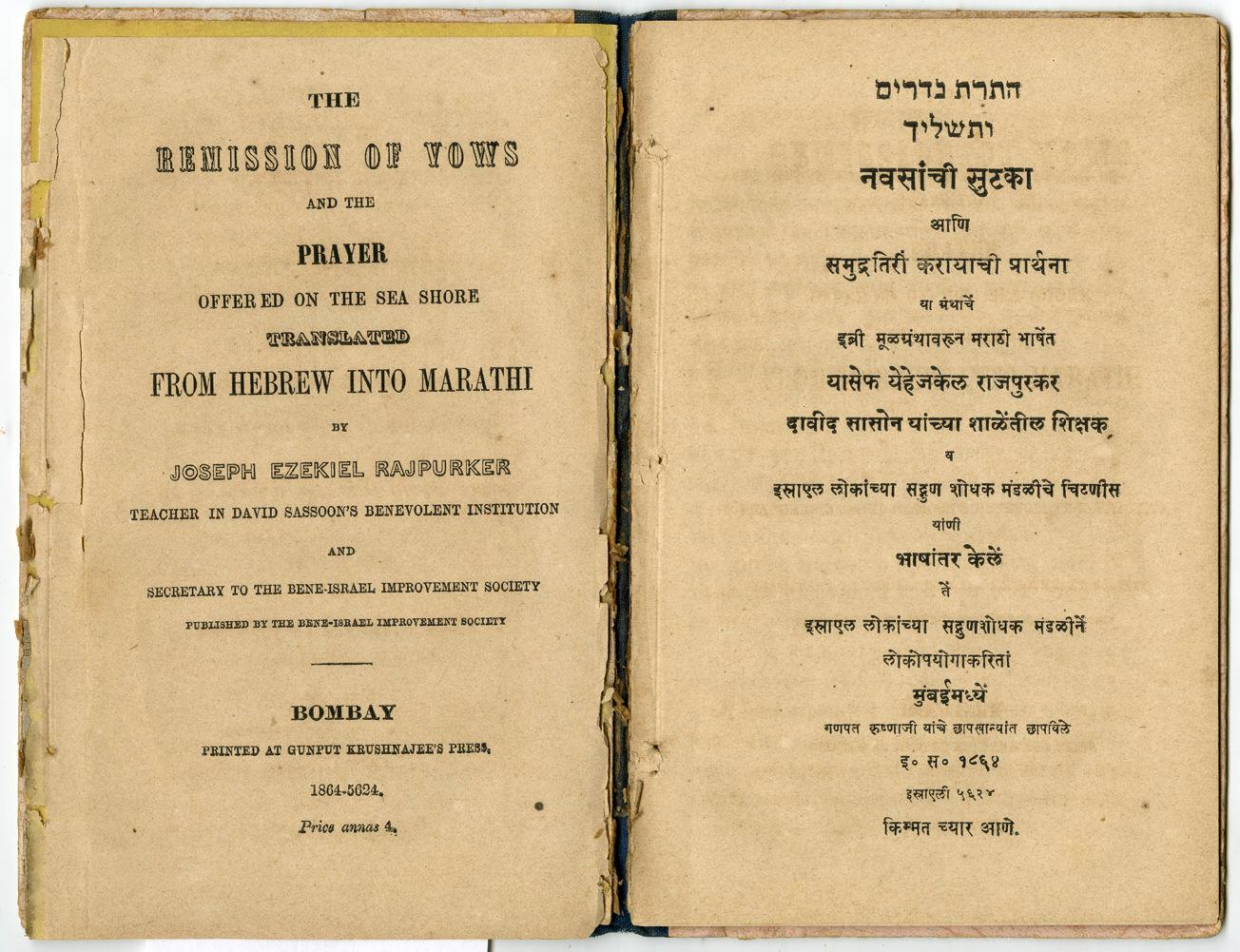

Little wonder, then, that over the years tashlich has held its own.

Little wonder, then, that over the years tashlich has held its own.