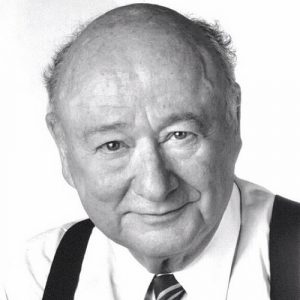

In the wake of former New York Mayor Ed Koch’s death last week, tears flowed freely. So, too, did references to a remarkable number of Jewish words, concepts and rituals.

Others made a point of characterizing Ed Koch as the “proudest of Jews,” and as a man distinguished, through and through, by his chutzpah.

Then there was the inside joke made by Michael Bloomberg. At Koch’s funeral at the majestic Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue and 65th Street, the current mayor began his remarks by saying how gratified he was that Koch had arranged to have his funeral at “my neighborhood shul.” How the 20th century grandees of Temple Emanu-El would have cringed to hear their monument to Reform Judaism likened to a modest, unassuming and decidedly East European synagogue.

It’s a measure of how far things have changed in contemporary America that Bloomberg not only made the remark in the first place, but also saw no need to translate the word “shul” into English: the reference stood on its own. A second, equally revealing, measure of change was the ease and familiarity with which Mayor Koch’s longtime Chief of Staff, Diane Coffey, publicly announced that “a shiva for the family” was going to be held at Gracie Mansion. No explanation necessary.

Elsewhere, the New York Times, for its part, indicated that “mourners, led by Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, will sit shiva for Mr. Koch at Gracie Mansion.” Did the Times get that wrong? Or had the current mayor just inaugurated a brand new ritual in which political figures publicly mourned the passing of one of their Jewish colleagues?

Either way, there’s no doubt that, in life and in death, Edward I. Koch took Jewishness to a whole new level, rendering it as public as a proclamation from City Hall.