I don’t envy future historians who will set out to chronicle modern Jewish life, ca. 2017. Swirling with contradictions, with a “this” for every “that,” it’s enough to make Tevye, Sholom Aleichem’s famously ambivalent character who delighted in routinely invoking “on the one hand” and “on the other,” run for cover.

Consider, for instance, contemporary attitudes towards the celebration of Shabbat, the traditional Jewish Sabbath. An age-old practice that has received a new lease on life of late, keeping Shabbat is increasingly associated with tuning out, with putting one’s smartphones, laptops and iPads to rest. As Reboot’s “Sabbath Manifesto” would have it, we digital devotees would do well to pledge to “unplug from technology regularly.”

Whether encouraged by Reboot or by the rabbinate, the Sabbath is hailed these days as an opportunity rather than a burden. Its latter-day promotion is reminiscent in many ways of the postwar campaign launched by the women of the Conservative movement to honor the Sabbath by pledging publicly not to do laundry, market, head for the golf course or the local museum and movie house on that day.

So far, so good.

On the other hand, there’s this: leading Jewish cultural institutions such as the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco, the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles and the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia now open their doors on a Saturday — and to paying customers. The decision to “operate normally,” explained a former official of the Philadelphia facility, reflects the “tension between freedom and tradition [that is] at the core of the American Jewish experience.” (The Jewish Museum in New York is also open on a Saturday, but admission is free.)

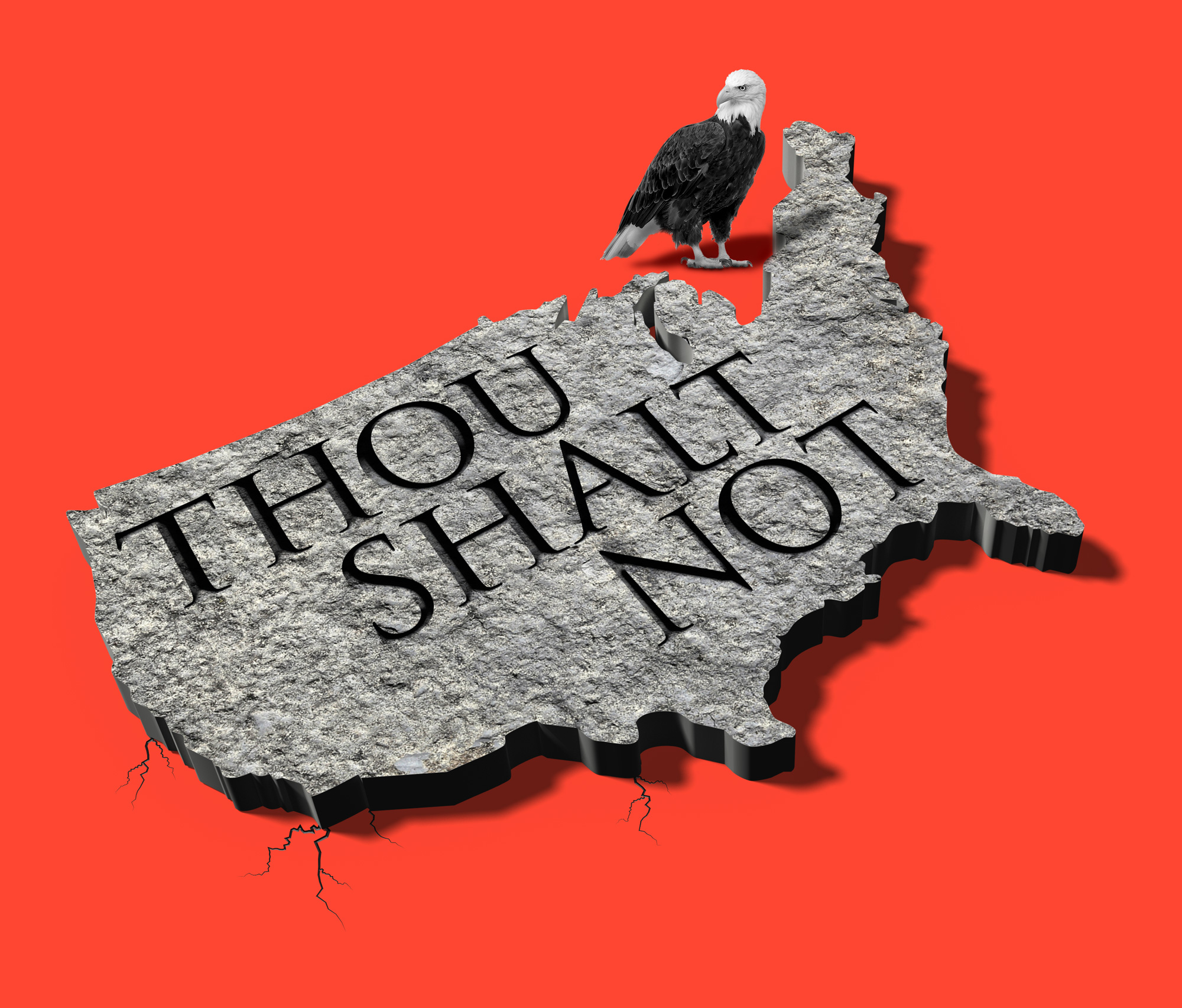

And this: Just the other day, Israel’s High Court ruled that over one hundred businesses — food stores, mainly — in Tel Aviv, would be allowed to offer their wares on Shabbat, overturning a longstanding municipal interdiction against commercial activity on the traditional day of rest.

Good news for some, especially those who’ve chafed under the heavy hand of halakha (Jewish law), this latest turn of events profoundly upsets others, raising the possibility that the Sabbath, once considered a “national asset,” will come to have a limited shelf life.

The jury is still out — and will undoubtedly be out for some time. We’ll have to await the verdict of history.